Marine phytoplankton, mass extinctions, and the importance of resting

PhD Sofia Ribeiro (GEUS, Maringeologi og Glaciologi) Modtager af Schibbyeske præmie 2014

Since photosynthesis evolved in the oceans more than 3 billion years ago, marine primary producers have been resilient to episodes of catastrophic environmental change across geological times, and have persisted throughout all major extinction events in Earth’s history. The most recent mass extinction happened 65 million years ago (Cretaceous-Palaeogene boundary) and is linked to a large asteroid impact resulting in prolonged darkness and a global collapse of photosynthesis (as well as the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs).

Marine phytoplankton, particularly dinoflagellates and diatoms, appear to have been resilient to this biotic crisis, but the reason for their high survival rates has long been debated. Many phytoplankton species produce resting stages (cysts or spores) as part of their life-cycle, which accumulate in marine bottom sediments over time and may be seen as the marine analogues of terrestrial “seed banks”.

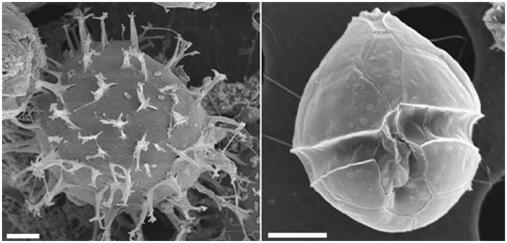

Resting cyst and vegetative cell of the dinoflagellate Pentapharsodinium dalei, the model species used in this study. Scale bars = 5 μm. From Ribeiro et al. 2011.

By reviving phytoplankton resting stages buried in datable sediment records, we discovered that these can remain viable for at least a century and that their growth performance (fitness) is unaffected by prolonged dormancy. Furthermore, intraspecific eco-physiological diversity is kept in the sediment record. These results indicate that phytoplankton resting stages can endure periods of darkness far exceeding those estimated for the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction and that “cyst banks” are crucial depositories of biodiversity, and may be responsible for a rapid resurgence of primary production after events of major ecosystem disturbance

Kontakt: Sofia Ribeiro - sri@geus.dk